17 Aug Jellyfish – Climate change indicators

Jellyfish have drifted in the Earth’s oceans for more than 500 million years and rare fossils have been found that predate dinosaurs. There are over 4000 known species and maybe more. Some new species have recently been identified in the Atlantic ocean.

What are jellyfish?

Despite their name, jellyfish aren’t actually fish—they’re invertebrates, or animals with no backbones. These are gelatinous animals drifting through the world’s oceans with pulsating bells and long trailing tentacles, part of the Cnidaria family, containing jellies, sea anemones and corals. There are also pseudo jelly fish such as the Portuguese man o’ war which is in fact not one organism but a large colony of siphonophores. The simple digestive cavity of a jellyfish acts as both its stomach and intestine, with one opening for both the mouth and the anus!

As jellyfish squirt water from their mouths they are propelled forward. Tentacles hang down from the smooth baglike body and sting their prey.

Some facts:

- A group of jellyfish is a swarm or smack

- Jellyfish are 90% water

- Most jellyfish live anywhere from a few hours to a few months although one species is possibly immortal

- There are also organisms called comb jellies which are a different family to jellyfish but look similar.

- They don’t have brains, heads, hearts or bones; just a network of neurones that allows them to sense their environment, temperature, touch, whether they are up or down and light levels.

Increase in jellyfish sightings

You may have noticed that over the past decade, the sightings of jellyfish around both the Channel islands and the south coast of England have increased. Different types of jellyfish can be found in different temperatures, so identifying the species off the coast will give an indication of ocean temperature and therefore indicate climate change. Scientists think that the jellyfish are increasing due to predators being removed by overfishing, the warmer waters enable them to grow more quickly, waters are more nutritious due to fertiliser run off (quick question – does the smelly sea lettuce covering on the Jersey beaches accompany an increase in jelly fish sightings?) and man-made platforms in the sea which allow jellyfish to settle and spawn. All these lead to jellyfish blooms.

Can we eat them?

Jellyfish are carnivorous and eat plankton with some of the larger ones eating fish and crustaceans. Lots of sea creatures also eat the jellyfish; ocean sun fish, leather back turtles and over 150 other animal species as well. Even humans eat them and they are a delicacy in south east Asia.

Sesame Jellyfish salad

Sesame Jellyfish salad

Identify Jellyfish

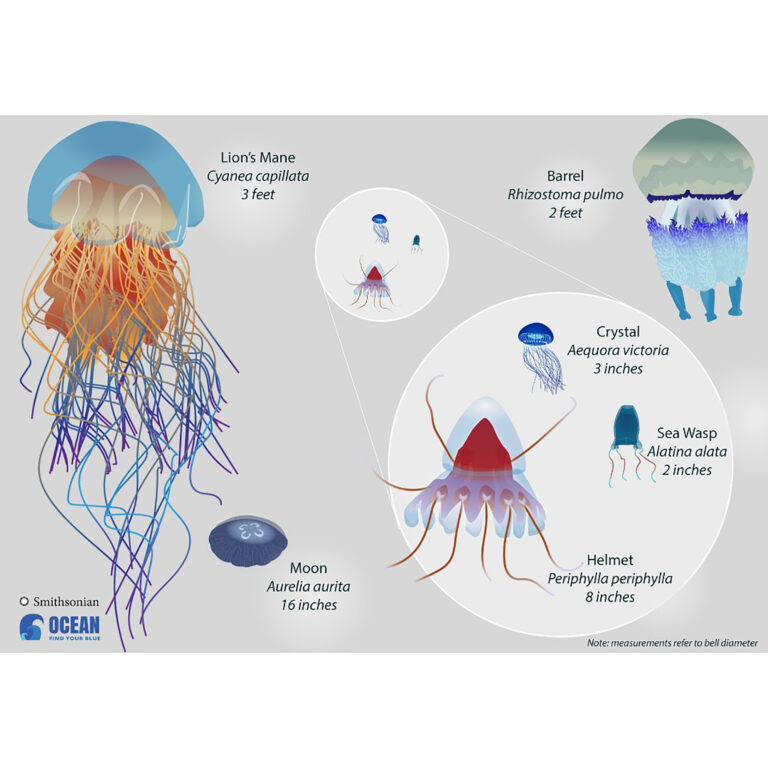

Common Jelly fish around our island shores ( Credit- all images taken from the Marine Conservation society page)

Barrel Jellyfish (mild sting)

Blue jellyfish (mild sting)

By-the-wind-sailor ( not a jellyfish but a jelly comb)

Compass jellyfish (painful sting, may require medical treatment)

Lion’s mane jellyfish (painful sting may require medical treatment)

Mauve stinger jellyfish (similar to stinging nettles)

moon jellyfish (mild sting)

Portuguese-man-of-war (very dangerous for humans but rare in our waters)

The marine conservation society are keen to collect data on the jellyfish around our coasts.

You can report a jellyfish sighting here https://www.mcsuk.org/what-you-can-do/sightings/jellyfish-sightings/

What to do if you get stung by a jellyfish.

Jellyfish have tiny stinging cells in their tentacles to stun or paralyze their prey before they eat them and can sting even when they are dead. Jellyfish stings can be painful to humans and sometimes very dangerous. But jellyfish don’t purposely attack humans. Most stings occur when people accidentally touch a jellyfish, but if the sting is from a dangerous species, it can be deadly.

A group of scientists from the University of Hawaii tried out different methods to see which would be the best to apply to a jellyfish sting site. This is what they found:

- DON’T Rinsing with seawater spreads the sting to a large ares (however this is recommended by the NHS.) It is likely to be the only water available to you so if using it make sure you have isolated the sting area and the seawater is not washing off onto any other part of the body.

- DON’T Scraping off the tentacles with a credit card applies pressure causing the stingers to release more venom

- DON’T Urine doesn’t do much- the consistency of urine is variable and depending on what you have eaten it might make it worse

- DO Rinsing in vinegar will deactivate the stinging cells ( however this is the only instruction from this list which is not recommended if you check the NHS website)

- DO pluck off the tentacles with tweezers carefully so you don’t activate any more active stingers

- DO Add heat/hot water which will help deactivate stinging cells

Most stings from sea creatures in the UK are not serious and can be treated with first aid. Sometimes you may need to go to hospital.

Get help if possible

Ask a lifeguard or someone with first aid training for help.

If help is not available:

Do

- rinse the affected area with seawater (not fresh water)

- remove any spines from the skin using tweezers or the edge of a bank card

- soak the area in very warm water (as hot as can be tolerated) for at least 30 minutes – use hot flannels or towels if you cannot soak it

- take painkillers like paracetamol or ibuprofen

Don’t

- do not use vinegar

- do not pee on the sting

- do not apply ice or a cold pack

- do not touch any spines with your bare hands

- do not cover or close the wound

Go to a minor injuries unit if you have:

- severe pain that is not going away

- been stung on your face or genitals

- been stung by a stingray

Immediate action required: Go to A&E or call 999 if:

you’ve been stung and have:

- difficulty breathing

- chest pain

- fits or seizures

- severe swelling around the affected area

- severe bleeding

- vomiting

You may have also been stung by a weaver fish, sting ray and sea urchin.

I have never been stung by a jellyfish, and this is not “you must do or not do” advice but reporting back on what other reputable organisations recommend. I do generally wear waterproof shoes when I go into the water.

References

https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/invertebrates/jellyfish-and-comb-jellies

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/14-fun-facts-about-jellyfish-67987765/

https://www.mcsuk.org/what-you-can-do/sightings/how-to-identify-jellyfish-sighting/

https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/facts/jellyfish

https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/how-identify/identify-uk-jellyfish

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/jellyfish.html

http://www.beachstuff.uk/which_jellyfish_sting_.html

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.